1: Nowhere

Sometimes you’ve got to learn a thing to break a thing, like a jazz musician who learns the rules only to fuck with them; other times it’s fresher to learn from necessity and urgency, with no practical skill base at all - more a punk sensibility - to strap it on and see what noise you can get out of it.

1big1

I often look to specific trades or skills in making sculpture, referring implicitly to respective histories alongside unconventional outcomes, and an awareness is frequently needed to keep the craft where it's needed, and not where it overrides the idea. In short, possessing relative skill in making can be very useful, but also a nagging barrier to ‘new’ thinking, learning and doing: a temptation and ability to do things skilfully or ‘properly’ (gah) can get in the way of communicating an idea. I see this in teaching, too: it’s exciting to enable a fellow artist/designer to learn ‘just enough’ to then make something that wouldn't have otherwise existed in the hands of a specialist.

I teach woodworking and sculpture for a living, but it’s not often that wood itself features in my own artistic practice. Maybe it’s because of familiarity and fatigue, alongside a habit for negating the time it takes to be a bit crap at something, to then get as good as necessary for the work, without it getting clouded by thinking of it as ‘woodworking’.

Eventually furloughed some weeks into the crisis, I steamed into a now-familiar routine of institutionalised daily rhythms, punctuated by the absences of context, and underscored with a deep fear and anger that occasionally also produced days of inactive nowhereness. ‘Productivity’ (later becoming a kinder ‘activity’) seemed a modest goal for the preservation of my mental health, which I considered at far greater risk than physical, once the dissonances, insecurities and the relative financial privilege of furlough were recognised.

I started out on something shortly after lockdown commenced, based on contemporary/ancient apotropaic (protective) markings, keeping me occasionally busy when the world falling down wasn’t occupying my head. When all this started, I had what I had at home. Though I keep a studio, I thought it better to see how it went where I was, to make do. Many of the things I couldn’t then get hold of, I now can, but I’m still not wild about shopping trips. I’m enjoying making things as simply as possible for a change. The necessity of constraint made me think of Samuel Beckett’s scripts written deliberately in a language he didn’t speak fluently: increased efficiency of communication though lack of detail.

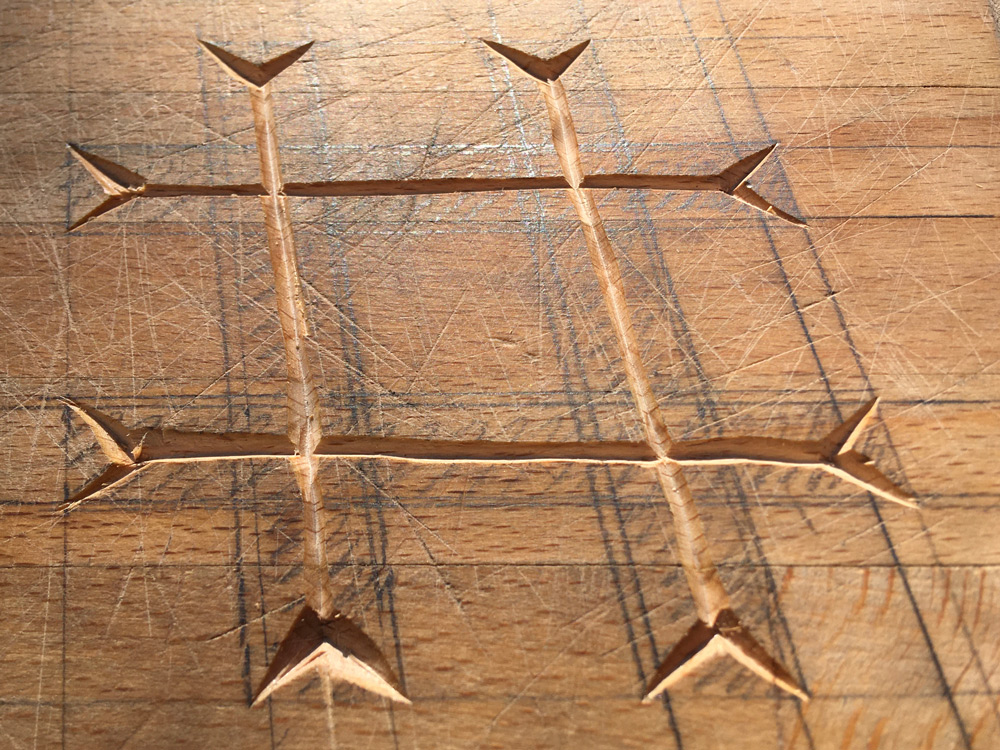

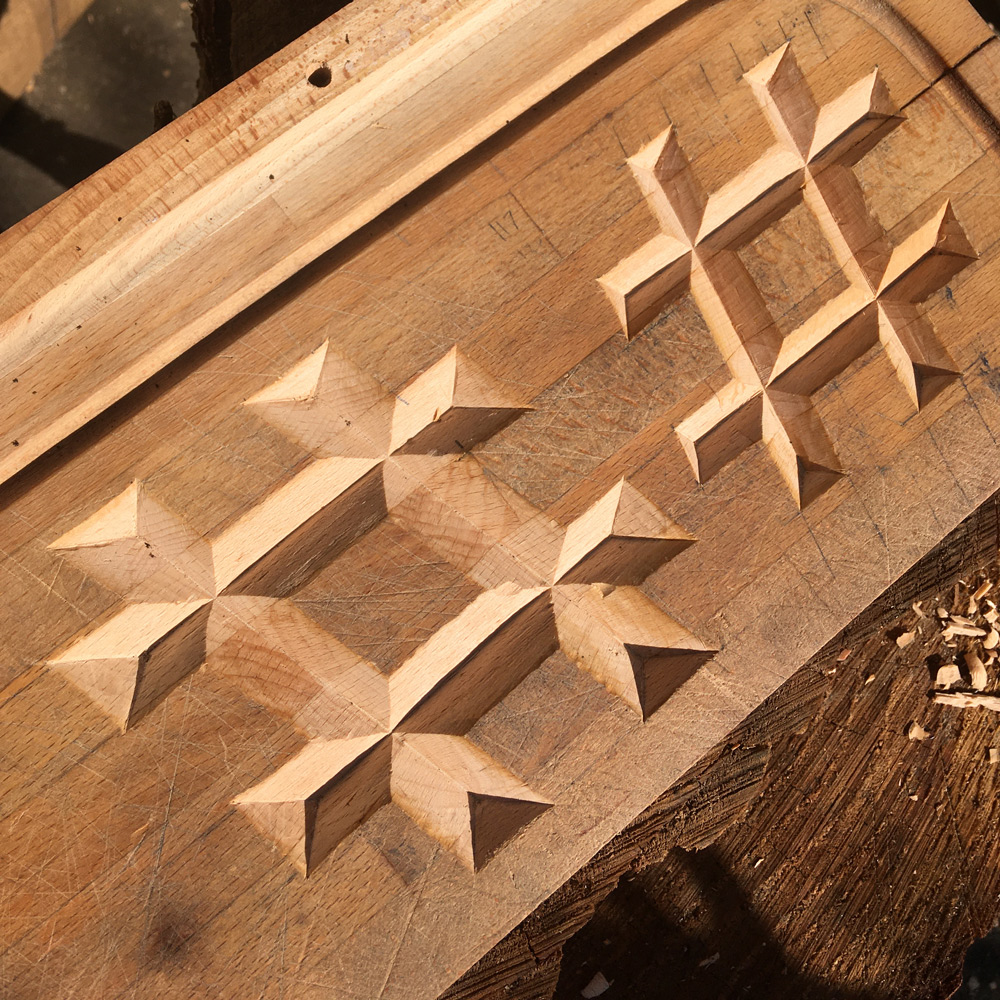

I started with some old chopping boards in beech and pine, as well as Welsh birch logs and some axe-split contorted willow from next door’s tree, marked out loosely and carved into using one of the few sets of tools at home with me: my grandad’s patternmaking chisels, which are probably getting on for about 80 years old, pretty fiddly, but fucking great; some times feverishly hacking away, others spending what became hours of technical learning by doing.

Carving these patterns into the surfaces every once in a while, and sharpening the tools, has helped me to ‘keep my hand in’ by concentrating on a small thing, whilst other ways of thinking and doing are less accessible. It’s also helped me make things a little less complicated and exacting than I might ordinarily default to as a way of making/avoiding making, as well as trying not to spend all day everyday online. At my shared house we've a small garden, for which I’m very grateful, mostly as a place to make mess; dusty, chippy or smoky; but also for the sounds, space and shifting of the day’s sunlight which marks the time passing.

The hashtag or crosshatch is something that works for me as a form simple enough to offer endless variation, whilst still being graphically defined as having a strict format. It’s literally as old as humanity, recently being identified (by Paleoarchaeologist Genevieve von Petzinger) as one of the most commonly occurring prelinguistic signs in prehistoric ‘cave painting’ across the globe, and has had many names, uses and iterations since. Over the passing weeks I varied the size and precision, as well as technique and style, to make each one unique, and to try standard methods learnt from YouTube, but also just seeing what worked, and what didn’t.

2: Absolution

About six years ago I saw these lead crosses at the Science Museum in London. They’ve stuck with me ever since, probably one of the most brutally striking and curiously ugly/beautiful things I’ve ever seen in a collection. They’re variously described (online) as ‘mortuary crosses’, thought to be from the time of the European Black Death of 1348-53, as well as the subsequent Great Plague of 1665, and were found placed on the bodies of those who succumbed.

[Image: Wellcome Collection, Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)]

Due to the huge quantity of victims, it was thought that the crosses were knocked out quickly and in massive numbers, to offer absolution for the departed souls of those whose lives couldn’t be saved, before all being buried together in huge pits. Found with their skeletal recipients in the early 20th Century during the excavation of a London cemetery, near the site of the old Grey Friars Monastery, it looks as though the crosses were in fact most likely made for “prisoners from nearby Newgate Gaol who had died of ‘gaol distemper’, or typhus, in the 1700s”. The archaeologists who carried out the recent revision work over 100 years later, Barney Sloane and Bruce Watson, tracked down 89 crosses, through museums British, Science and London, as well as the Wellcome Collection, alongside archival documents and maps.

[Image: Science Museum Group Collection, The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum]

Two things in their study (‘Crossed Wires’, 2005) caught my eye. Firstly, as the sculptor at home in a pandemic:

“The crosses were probably cut from sheet lead by knives (not by shears or chisels). In many places this process is marked as a series of short, jagged cuts. One cross (the image above) shows evidence of having been cast in a very crude and leaky mould, with very substantial amounts of flashing remaining between the cross arms and no evidence of having been cut, milled, or hammered.”

Secondly, their amuletic purpose, for the anxiety and frustration stilting my every creative thought, at an unbelievably sad and terrifying time:

“The inclusion of lead crosses in medieval graves has been interpreted as a means by which the bodily remains could be protected from demonic possession, or by which the deceased might exhort any who disturbed their bones to offer intercessory prayer to hasten their souls through Purgatory.”

3: Older Abnormals

And so, to these, an ever-growing series made from repurposed antique Sheffield Pewter.

[Image: Science Museum Group Collection, The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum]

The intaglio carvings in wood took on a life of their own, but were made for this eventual purpose, as moulds. I was thinking about those mortuary crosses a lot. I’m not much for faith myself, but making these felt like a reasonable successor; something tactile, made and to make, to hold on to for some sort of transformative, productive, protective activity. As much of the world stopped holding, touching and speaking in person, we all looked immediately to online networks and intersections for communication, delivery and deliverance.

In breaking down, melting, pouring and crystallizing, it’s not just the metal that changes form; the moulds themselves degrade and burn a little with every use. Each pour only stays hot enough to flow for seconds; sometimes the accuracy wobbles, bringing about some flashing and overflow, making each cast unique. They're pictured ‘upside down’, for the impression of the carved moulds. This is quite standard in open mould casting - the ‘upper’ face is often featureless or a bit gloopy, and I enjoyed learning that it doesn’t matter which way they’re italicised, carved or drawn: flip them, tilt them through 90° and they’re mirrored. They remind me as much of Billy and Charley’s mid-19th Century ‘medieval’ forgeries, as of cheap band logo necklaces I wore as a teenager.

Lead’s easy enough to come by, but I had a stockpile of old pewter pint pots, which I thought I might use instead. ‘White’ metals such as these work fine with a blowtorch or stovetop (as I’ve no furnace in my garden... yet. Most of these are broken down, melted and poured individually in an old saucepan, the early ones heated in a tin can (asda chopped tomatoes) on a little campfire; the larger ones roughly equivalent to one whole jug. The pewter, mostly made of tin, is old and often low-grade, and has some lead in it as a result - it’s only relatively recently it’s any ‘safer’ than it was in the Bronze Age. It was odd to have an extra reason for wearing masks and washing hands at a time when I was too anxious to leave the house.

More recently, I made a two-sided cast, curious as to how one of these forms would turn out from closed mould, rather than a levelled, open-faced one. I had no flat boards left, so I used some chunks of 4” x 1” sapele hardwood that had been in my garden since before I moved in. I used an old block plane to smooth down one face and marked them up with the mirrored shape - neither piece was square at all, chewed off with a handsaw from the planks. Sapele is wonderful, I’m told, for making door and window framing. It is, however, fucking horrible to carve: really splintery and harder than oak.

I’ve done this kind of carved, two-part mouldmaking for metal pouring before, in cuttlefish bone: then, the powdery carbonate falls away easily with scraping, but as with this mould, registering the pieces to each other is a challenge. I cast it a few times to get one without serious pitting, but not much flashing overall, considering. I heard the fabled ‘Tin Cry’ a few times (a squeaky noise emitted when a tin alloy is twisted), which was a bonus I’d forgotten about.

The hashtags, once cooled, are reassuringly heavy in the hand, glittery, scarred and with a surface that shifts in the light. They were described by a friend as an imagining of rave fliers that might emerge in Russell Hoban's ‘Riddley Walker’, which accounts for their title, ‘1big1’ in alluding to the aftermath of a cataclysmic global event as much as a big night out.

There’s something to be said for speculative imaginings of how a post-apocalyptic community in a distant time might survive and make do, as the normal ways of feeling, creating and relating are switched on us. In recent weeks, we’ve all discussed our sculptural conventions; why we revere, make permanent and monumentalise that which we do: the acts, figures, forms. There's also been very real grief, suffering, and continuing bouts of confusion as things, people and directions grind against each other, in individual attempts to return to something recognisable. Using making as a method of preservation in itself, and looking to older ways of thinking and doing, I’m leaning not towards this ‘new normal’ we hear about, so much as a reimagining of ‘older abnormals’: times when those who came before us might feel a need for connection and protection beyond the immediately tangible, whilst dodging dissociation in making as a method of my staying in the present.

Sometimes I stop myself from making things because I feel a better idea or form is around the corner, ready to flatten this one so I can make something ultimately superior, at a point further in the future. This almost always results in an enormous amount of research and very little doing; the knowledge is never not fascinating, it feels very necessary. That said, if not incorporated as helpful daily nuggets of wisdom towards the manifestation of artworks, research alone leaves me ultimately frustrated. A practice is just that, and is as true for life in general as it is for creative work. The routine, at this time, has been a simple thing that’s easy to forget, but thankfully easy to remember again: keep up your daily moving about, the little joys, a stillness and quietness as it’s felt, communicating as necessary. As science-fiction author Octavia E. Butler’s ‘Furore Scribendi’ holds:

“First forget inspiration. Habit is more dependable. Habit will sustain you whether you’re inspired or not. Habit will help you finish and polish your stories. Inspiration won’t. Habit is persistence in practice.”

This article comprises several communications and instagram posts from April-June 2020, at

@tom_railton; further work can be found at

tomrailton.com

Many of the hashtags made in this manner are available to buy, as part of the

Artist Support Pledge; get in touch via my instagram if you’d like to talk or to buy one, I’d love to hear from you.

Unless otherwise stated, photos all author’s own.

By Tom Railton